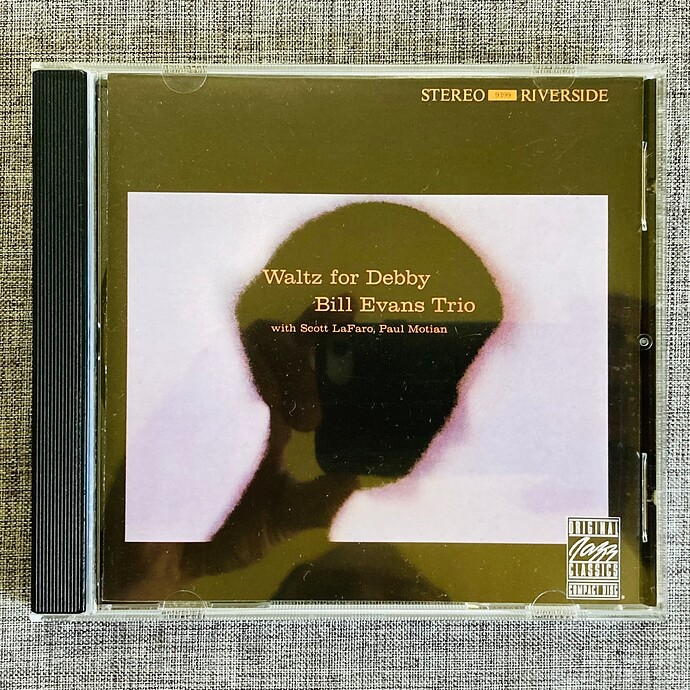

It’s Sunday and I’m listening to this, the twin album (released half a year later) of Sunday at the Village Vanguard , both recordings culled from the same live set at the famed jazz club on June 25, 1961.

This is one of my favorite albums. I used to listen to it through my Amazon Music account but found out one day that–for some inexplicable reason–it was gone. No explanation; it just wasn’t there. I learned that day that you don’t really “own” your digital music, you just “rent” it.

So I bought my very own physical compact disc and a CD player to play it so it won’t be lost, unless somebody breaks into my house and steal it, or some horrible disaster befalls the Kanto Area of Japan and destroys my CD collection.

Joe Goldberg, in his liner notes writes:

I find this a fascinating album in several respects. One of the most intriguing certainly is the way in which it demonstrates how Evans, who came to prominence largely through solos played or recorded with such men as Miles Davis and George Russell, abandons, to a great extent, the muscular rhythmic excellence of such performances when he is leading his own trio, and gives expression to the more romantic side of his nature. He reveals himself as an Impressionist: and the man who wrote the brief and lovely Epilogue (included in the album Everybody Digs Bill Evans) must have been influenced by the English pastoral composers. In some respects, Evans shares identity with the Modern Jazz Quartet: both groups could probably play all night long, and a drunken listener would never know that he had heard anything more than quiet, pleasant cocktail music.

A word about LaFaro: at his death, he was one of the supreme jazz bassists. Those very few men who have done anything to change the conception of the bass have seemed to consider it as some other instrument. The Blanton Ellington duets (which are in some ways the spiritual progenitors of these recordings) achieved much of their effect through Blanton’s bowed passages, which sounded like violin or cello work.

The work of LaFaro (which at one time stemmed quite directly from Charles Mingus) often sounds as though he were playing a large guitar: one solo he has recorded is astonishingly like Django Reinhardt. Like Mingus, LaFaro’s ideas could only be played by a virtuoso; also like Mingus, the virtuosity is never more than a tool to convey the idea. But they are exclusively virtuoso lines, requiring complete technical mastery to execute. Aside from the guitar conception, there is a much more basic advance which LaFaro (and other bassists such as Wilbur Ware and Charlie Haden) are helping to initiate: prior to them most bassists were so steeped in their roles as timekeepers that, during their solos, they would simply continue to keep time, only with a more interesting choice of notes. LaFaro had completely freed himself from that constriction, and it undoubtedly took a sensitive, unobtrusive drummer like Paul Motian to help him do it.

The Penguin Guide to Jazz awarded this album their coveted crown.